Colorado Poets Center E-Words Issue #6

Inside issue #6:

Interview: Stephen Beal, Art and Words

BK: Let me start with your credentials which are impressive. Your embroidered canvases have been exhibited internationally for more than twenty years. You won the Lillian Elliott Award for Excellence in Fiber Art in 2008 and two pieces appeared in a fiber art exhibit at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City as well as being held in several museum and private collections.

Stephen Beal

You’ve written several non-fiction books but you’re also a poet. Each poem in your first book, The Very Stuff: Poems on Color, Thread, and the Habits of Women (Interweave Press, 1994) which won the Colorado Center for the Book Award in 1997, is inspired by a shade of embroidery floss you use in your work. Your most recent book is Suddenly Speaking Babylonian (Hanging Loose Press, 2004) doesn’t involve visual art but many of your themes are there as well.

So, now to you. On your website (www.stephenbeal.com) there are, among a lot of embroidered pieces, three poems and two stitched poems. How do you define your work in regards to language and visual art?

S.B: I don’t make a distinction between words and visual art. I put in words when they help viewers understand/appreciate/enjoy the image. But there’s another point—sometimes the words ARE the visual art. I envy the Japanese for their beautiful characters that are themselves works of art.

In “Sixteen Blocks,” I thought of a poem at three in the morning, did not get up and write it down (who does?), and miraculously remembered it clean and whole the next afternoon. I never planned or sought to publish it as words on paper; I knew right away that it deserved a canvas of its own.

BK: That’s the piece “Sixteen Sky Blue Blocks of Isolation” where there’s a quatrain embroidered on each block on a larger canvas. I couldn’t read it from the .jpg I got.

SB: It goes:

I want to reach out and touch

someone.

As long as t he touch is

welcome.

Some people are standoffish.

Like me.

I mean it. Tomorrow I will

reach out and touch

someone.

We will form a significant

relationship.

We will go places together.

We will watch the sunset.

Unless I get a crook.

Someone who steals my money.

Squanders my heart.

Takes the cat.

All in all I’ve got a good

life now.

I don’t mind being by myself.

I know what to expect

And how to dream.

BK: So that’s what I’d call a ‘written’ poem, only it’s embroidered as a piece of visual art. In “Picture Windows” there’s a slightly different take on a visual/word aspect. In that piece, you have a Rocky Mountain landscape as the scene with a line at the top )”The wealth that goes to make our picture windows”) and a completing line on the bottom (“proceeds from the destruction of our views”).

SB: Yes, I came up with those two lines in the 1960’s, for Lord’s sake, and never found the rest of the poem for them. I was living at Ragdale in Lake Forest, Illinois, teaching at LF College, at least a decade before it became the artist/writer colony, in the company of two of the aging daughters of the founder/architect of the estate. I was so lovely there and, already in the early 1960’s, so potentially threatened. I kept thinking I’d get more of a poem but, I guess, the two lines said everything I meant.

So I have used them to frame an ecological statement expressed in art. This was for me, once the idea came forty some years later, an immediate melding. I did not think, I’ve got these two lines, how can I do a picture with/for them? I simply—this is true—got the idea for an image to illustrate the lines, then went to the Yellow Pages and found a aerial photographer whom I hired to shoot the front range for me. Then I used some of his photos for my canvas.

BK: And there’s a band of four square ads superimposed over the mountains, each with a different message: “Do you have a picture window?” “Bet your neighbors have a picture window!” “Shouldn’t you have a picture window?” “Do it now? Order your picture window!” This is an interesting piece with several tones to it, it seems to me.

So, you were saying, sometimes words are the visual art itself. At other times, you use them like titles such as the one with embroidered portraits of Lincoln and Whitman and the text “When Lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d” stitched around and over the images.

SB: I’m essentially a storyteller, whether in art or poetry or fiction. So I put words in a canvas when they complete the story. In that case, I figured that some folks would not know the Whitman/Lincoln connection, or, for that matter, Whitman’s poem. So I put in the words to explain why I was depicting Whitman and Lincoln together.

BK: There’s another use of language in some of your pieces that I find serious and funny at the same time. For example, there’s a piece titled “Blood on the Linoleum” which has a red-headed woman fleeing the scene of a murder. In the piece itself are the words: “Tossing Her Titian Tresses, Susan Hayward Screams.” So I wonder if you did the visual and then wondered what was going on or what. Does an idea come to you first in language or in visual design?

SB: Implicit in what I’ve said is that the words and the image usually come together. I don’t make a distinction between words and visual art. I put in words when they help viewers understand/appreciate/enjoy the image. There has been only instance in my work when the demands of visual art dictated the use of words. In “They Were Young” I realized that I had a hole in the middle of the canvas without the placard announcing the cast – Picasso, Stein, etc. That was the only time.

BK: One more thing. I notice, and this is true of your poetry, certainly in Suddenly Speaking Babylonian, that the people in your work are often famous artists or historical figures.

SB: That’s true. What I love is entertainment, both entertaining and being entertained. Stein, Toklas, Picasso, Matisse, that period of Parisian history intrigues me no end. Flaubert is one of the funniest men I’ve ever encountered, probably despite himself. His letters to his Parisian mistress Louise Colet are masterpieces of obfuscation and subterfuge. He never did marry her, and Louise almost died from rage.

Joy is another way to put it. Poor Vincent: I like to try to GIVE him some joy, some relaxation, some release. I have a feeling he may still be all twisted up in heaven. Like Louise Colet, poor dear.

Heightened experience is another draw for me, and, I suppose, that may well be a province of the well-known and famous.

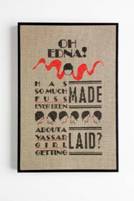

“Oh, Edna!” A Visual poem by Stephen Beal