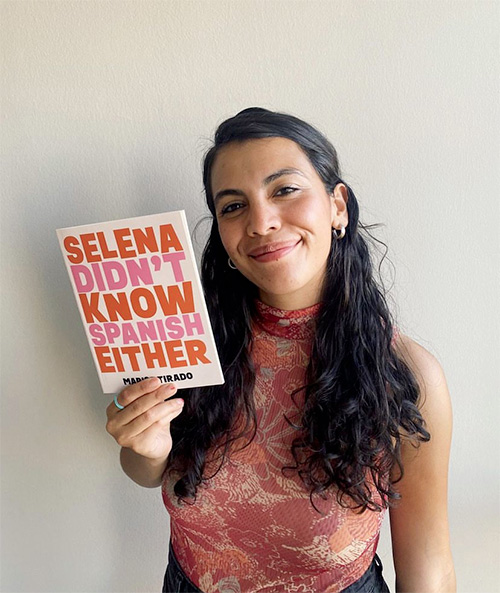

An Interview with Marisa Tirado

Marisa Tirado is a Chicanx and Latinx-Indigenous poet from Chicago with roots in New Mexico . She recently published her first chapbook, Selena Didn’t Know Spanish Either, winner of the 2021 Robert Phillips Chapbook Prize, (Texas A & M University Press). She has an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her work has been published in journals such as The Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, and TriQuarterly. She is the co-founder of Protest Through Poetry, an international collective of BIPOC activist poets and currently teaches at the University of Colorado.

KW: I want to talk about the organization of your stunning chapbook, Selena Didn’t Know Spanish Either. I’m always interested in the genesis of a poetry collection, of where a collection starts, of how poems begin to bump into each other and threads begin to form. For instance, the poem “di-as-po-ra,” acting as an epigraph before the table of contents, so perfectly foreshadows what is to come in the book that I wonder if the poem came before or after the completion of the chapbook. Three poems, each titled “Young Memoir,” make up an interesting extended thread throughout the book. The title poem of the chapbook shows up about three quarters into the book; travel poems appear as you search for your heritage and culture; part of the chapbook is about searching out the mother language you were never taught, yet the book never becomes a “bilingual” book, perhaps in reaction to the “bilingual teen” who warns you of your “pending reduction.” In addition, the book is forty pages long: what made you decide to keep the book as a chapbook rather than working on extending some of the threads already present in it and writing a full volume of poetry? In other words, spill the beans on creating this chapbook.

MT: This chapbook was a crash course in my understanding of how to thread a manuscript together. The original manuscript was actually 20 pages longer than the final published book, and the first working title was How to Make an Adobe Brick, focusing on both the physical and abstract making of a self. However the brick’s material “layering” I was looking to explore was too ambitious—it talked about religion, COVID, etc—it was too vast for a shorter chapbook structure.

In learning how to create cohesion within a collection of diverse pieces, I started to study not poetry collections, actually, but art exhibits. I was living in Europe at the time and had the opportunity to study exhibits at the Prado and the Leopold Museum in Vienna. At the Leopold I was especially taken by a Tracy Emin exhibit. Her work uses multiple mediums from textile to video, shaped both by tragedy and humor, exploring hopes, humiliations, failures and successes…yet each piece felt so cohesive and familial to the next. Though I did not accomplish this even near to Emin’s degree, that clear thread among distinct pieces is what I will always aspire to in my manuscripts, including this chapbook.

Also, never underestimate your trusted readers. My poet friends and workshops were undeniably helpful in line edits and ordering. When it came down to final adjustments before submission to Texas Review Press, the chapbook still felt patchy for some reason. That was when I remembered poet laureate Ada Limon’s visit to our Iowa Writers’ Workshop cohort, during which she said something that quite countered what some of my advisors prescribed: it’s okay to write poems with the purpose of filling holes in a manuscript. That advice allowed me to write in poems that gave the book a sense of completion (resulting in poems such as “di-as-por-a”).

KW: I find that thread of poems titled “Young Memoir” interesting because so much of your chapbook isn’t directly about you. As a matter of fact, the approach you took in exploring your mother’s history and culture that your parents seemed to have symbolically kept from you in their decision not to make you bilingual reminds me of the work of the poet laureate Natasha Trethewey, author of the Pulitzer prize winning collection of poetry, Native Guard. Trethewey researched the erasures in history and discovered revelations of her personal history through lost public history. Much of the discovery of the maternal side of your culture comes from what you learn from the stories and words of others: cousins, Lorena Bobbitt, salon girls and nightclub bouncers, the American Tejano singer, Selena. You are often, as you worry in your poem, Jalisco, MX, almost a tourist in your own life. Talk about what inspired the poems you wrote in this chapbook and why.

MT: My poems are inspired by, among other things, losses and wins and the curiosity that resulted in each. Our family’s paper trail ends in the 1920’s because of an Indian boarding school? Fine—let’s stick to oral stories of my mom being chased by cholas, that’s my archive. My grandmother never took me to her native down in Michoacan? Alright, I’ll visit my sister-in-law in Jalisco and try to feel some sort of self in the land and the familiar things I find (an accent, a smile, a rice dish). I get a year abroad in Spain? Let’s venture into the euro-centric alterations of the language and see what we find in being a brown person in yet another white environment. These emotionally curious experiences build up in the chapbook as I try to cling to pop icons like Selena and infamous legends like Lorena Bobbit as a means of seeing myself in them when nobody was working to provide any sort of complex representation growing up. Anger is centric in my poetry too. The more I explore the white gaze and what it has cost me, the more comfortable I am with anger as a “prima” in a way.

KW: The title of your chapbook, Selena Didn’t Know Spanish Either , has a pretty defiant tone to it. And it fits the journey of this book perfectly, I think. The first real revelation of your family history comes in the poem, “Mom vs. The Cholas,” in which you vividly recount the violence of your mother’s early life and her crossing the border. From there, you take us into the history of a hundred years ago and the rape and captivity of a matriarch by a Spaniard that “made [your] skin.” By the end of the collection, you “find anger everywhere.” I think the anger is literal, not literary, given that you have co-founded Protest through Poetry, an international collective of BIPOC activist poets. Can you talk to us a bit about the emotional stakes you discovered in writing this book, what compelled you to turn to activism, and what you hope to achieve through your collective?

MT: As an assimilated, model minority raised in a white, Midwestern suburb, anger was ground-breaking for me. I didn’t discover it until I was 22 and never looked back. Being a survivor/thriver in a white community when you are brown is to be as un-angry, and therefore, un-activist, as the two are always married, I would argue. But that anger can only be suppressed for so long. Now anger makes me who I am, it’s like a cup of coffee at the beginning of the day that fuels my ability to think clearly — which are liberating things to admit. I was taught to fear anger at first, not to mention there are very few places in the world that welcome anger from women, which are often quite patronizing (spin class, kickboxing, and like…sometimes wine night?).

Now feminine rage is my favorite thing to study, and I am constantly writing and exploring it. It’s a bit of a superpower now and gets shit done. Anger does not have to be unkind or violent. It should fuel us for changing systems and ourselves. In short, I recommend my readers to keep their anger close, and lean into their relationships to it.

KW: The Robert Phillips Poetry Chapbook Prize, publication by the Texas Review Press, reviews and interviews by places like The Poetry Foundation, publications in journals such as Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, TriQuarterly. a literary agent with Watkins/Loomis Agency! What’s next for you?

MT: My full-length poetry manuscript is in its editing phase! The book explores cousinhood and all its manifestations. What defines a cousin other than a diagonal relation to the self? We may be related to something, but still outside the main systems of immediate origin. This book asks the reader to recognize the various connotations of “cousin” beyond a family tree, into relations of history, justice, and religion. The speaker will consider how this particular tie to cousinhood exists within all the systems that surround us.

I am also currently working on a novel set in the Southwest. The story explores feminine rage, assimilation, and— my other passion— television narratives’ influence on our lives. The plot focuses on a waspy, white-washed Latina from Denver who returns to her mother’s lowrider small town in New Mexico to make a business deal. But the intense reimmersion into her culture and run-ins with her estranged family release complex emotions that trap her in a series of conflicts, keeping her in town longer than expected.

If readers want to follow my literary progress or buy a chapbook copy, follow me on Instagram at @marisatirado or visit marisatirado.com.