At Home in the Strangeness: David Mason on the Pacific Light beneath the Southern Cross

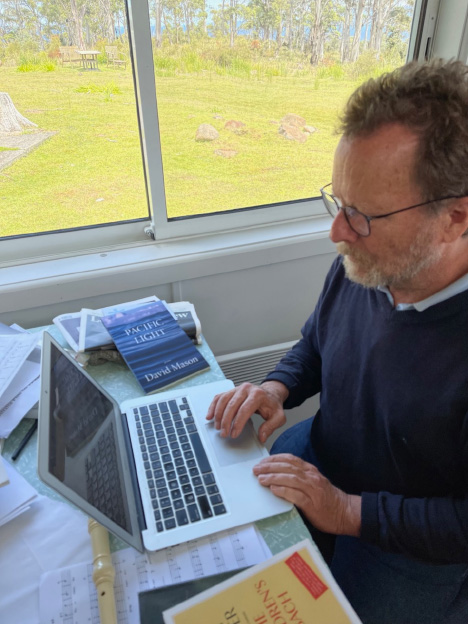

David Mason grew up in Bellingham, Washington, and has lived in many parts of the world, including Greece and Colorado, where he served as Colorado Poet Laureate for four years. He is the author of eight books of poetry including including The Country I Remember, Sea Salt, Davey McGravy, The Sound, Pacific Light (Red Hen Press) and Ludlow, which won the Colorado Book Award and was featured on the PBS NewsHour. He has also written a memoir and four collections of essays, of which the most recent are Voices, Places and Incarnation and Metamorphosis: Can Literature Change Us? (forthcoming in 2023). His poetry, prose, and translations have appeared in such periodicals as The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Nation, The New Republic, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Times Literary Supplement, Poetry, and The Hudson Review. Also an opera librettist, Mason lives with his wife Chrissy (poet Cally Conan-Davies) on the Australian island of Tasmania, near the Southern Ocean.

KW: When I finished Pacific Light, I immediately searched for a term, or even genre, for a type of poetry book written later in a poet’s life that looks both backward and forward in the contemplation of that life and its sure ending, the moment when the poet, like Hermes in your poem, “Words for Hermes,” is “the god of doorways,/of entrances and exits,/passages between.” Single poems, and the books they appeared in, came immediately to mind: Stanley Kunitz’ “Touch Me,” James Wright’s “The Journey,” Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.” Was I looking for simply elegy? In Memoriam? Even a kind of Hero’s journey? The poet Donald Hall uses the term “necropoetics,” in his essay, “ The Poetry of Death.” (There, btw, I found the beautiful poem, Twilight: After Haying, by his wife, Jane Kenyon, which shares your psychic connection with grass, as does Whitman, of course.) Pacific Light is a book of many immigrations, of a poet eyeing other horizons, among them certain death. Share with us your journey in writing a book that arcs so beautifully between the opening image of a husk of a huntsman spider found on a shelf to the disarmingly simple “Note to Self” and its culminating line, “Time to be grass again. Ongoing. Wild.”

DM: There’s an essay lurking in your question. I’m glad you see Pacific Light as hermetic—not so much inscrutable as multi-directional in its gaze. My “Words for Hermes” was written for a play that was never produced because the wonderful friend who commissioned it died suddenly, shutting the whole thing down. Death does indeed underlie nearly everything in the book, with its “many immigrations.” I’ve experienced a lot of death in my life, both the literal deaths of friends and family, and also the psychic deaths anyone faces in a life of change. But I don’t see death as a darkness. I see it as a natural process that gives meaning to literally every moment of our lives. Wallace Stevens wrote, “Death is the mother of beauty,” and that line from “Sunday Morning” has never been far from my mind.

I love Donald Hall’s essay, which you cite, because it reminds me that he was reborn when he married Jane Kenyon, just as I have been reborn through my marriage to Chrissy (whose pen name is Cally Conan-Davies). I became a better and a truer poet because of her, and my emigration to her home island, Tasmania, has been a deep enhancement of life and writing for both of us. I would not have made the move without the consciousness of death, the awareness that I had to seize what time I had left and make the most of it, because in my former life I was suffocating, living a lie. I was in danger of losing my life, in more ways than one, and now I have gained my life. There is no life without death, and also the consciousness of death. All poetics is necropoetics, even the poetics of joy.

KW: I once read/heard Kim Barnes, a northwestern nonfiction and fiction writer, talk about the writer becoming a “tourist” in their own environment and studying nature guides to learn the specific, beautiful names of the things they live amidst. And I remember a blog written by Colorado author Page Lambert, in which she shared the essential root-spring for her writing: the language of names that surrounded her home on the western slope. In Pacific Light, you have packed up and crossed the equator to the Southern Cross and a land “down under” in Tasmania on the edge of the Southern Ocean. So many of your poems touch on the search for words, for, what seems like a new authentic language, which is part of your new work, “the work no other demands in the light/we are given.” But this is no easy work. Pacific Light is about the search for language, a new language: “I have gone to school again. Learning to speak/without offending beauty, I have lost/ the language I was born to as I must.” I do feel that as Pacific Light progresses, so does your mastery of this new language, the new names of things rippling from your tongue deliciously: peppermint gum to pampas grass to whimbrels . . . Talk to us about what it means to take on a whole new environment and a whole new language where “the birds have not /forgotten how to sing . . .”

DM: Yeats wrote, “As I altered my syntax, I altered my intellect,” and he remains for me a great example of the artist who never stops growing and changing, never stops searching for the language he requires. For me, there has never been a barrier between the struggle to live a genuine life and the struggle to write well. I wrote Ludlow because I had lived 20 years away from the American West, and I needed to find a new language for myself as a Western poet. My most obvious example was Derek Walcott’s Omeros with its mix of languages, so I braided Scots and Spanish and Greek and English diction of various kinds in my poem—a deliberate attempt to match the multicultural reality of Colorado, the very cemeteries of a town like Trinidad.

Now that I have moved to Tasmania, I do indeed have a whole new vocabulary to learn, new vegetation, new insect and bird and animal life. Australia is both the youngest of civilizations and possibly the oldest—the indigenous society here represents at least sixty thousand years of continuous civilization. The government in Canberra is a mote of dust in that history, yet it wields most of the power here. There are parallels with American history and culture, not least the general American blindness to the fact of living, breathing indigenous people, the history of genocide, the efforts to find a path toward reconciliation. These are among the very things the human species needs to face for its survival on the planet, and they are part of everyday life and conversation here.

The social and historical parallels are real, and the geographical similarities between Tasmania and, say, the San Juan Islands where I spent my childhood, are also real. Our house here is almost exactly the same latitude south as our former house in Oregon was latitude north—nearly to the degree and minute. So I feel at home here even as I feel a stranger—at home in my strangeness, a condition I have known all my life. When I was 19 I wrote in a journal, “My place is to be out of place and to write about it.” I did not know how prophetic that line would be.

KW: Your words do not just live statically in your books. For years, your work has been entwined with so many types of media: screenplays, and operas. For Pacific Light, you created a marvelous YouTube video, Pacific Light: Poems of Renewal. Can you talk about your work in, for better words, multimedia/ the visual arts? What have you done? How did you get started? What has been the challenges? The rewards? What advice might you have for the poet wanting to “enlarge their footstep” in media?

DM: I wrote fiction before I wrote poetry. I wrote and acted in plays when young. I made up tunes and sang, and had to make up my own words because, due to my hearing loss, I never knew the words to other peoples’ songs. I did, however, have a lot of poetry and prose and drama memorized, so the formalities of art were never disconnected from voice and performance.

One of my unpublished novels was optioned by a film company when I was 25, and I got a small glimpse of what I thought would be the life of a full-time writer. Just this year, my verse novel, Ludlow, has been optioned by an actor hoping to produce it. I know enough to let him run with it as far as he can get. Lori Laitman is writing a beautiful opera based on the same book, and already several arias from that work are making a big impact in the singing world. My other opera work has all been commissioned, both for Lori and for Tom Cipullo, another composer I love. Poets often lead isolated lives, never hearing that their work is wanted by someone else. To be commissioned to write something—anything—is a great gift. With opera, you have the luxury of thinking through the lyric and dramatic problems you face, working them out in collaboration with other people, then seeing great musicians bring them to life.

The film you mention was made by a dear friend, Anna Cadden, but it was the brainchild of my wife, who had the vision to make it the way we did. Her genius and Anna’s brilliance make the film what it is. To poets I would say, don’t be afraid of such collaborations. Accept any challenge you can to bring your voice and your work to a larger audience. But don’t be afraid of obscurity either. Be as brave as you can, and write as you must.

KW: Favorite question, always: exemplary career, exemplary awards, exemplary work. What’s next “this day of the endlessness, day of the blue”?

DM: I’ll have a new book of essays out in March: Incarnation and Metamorphosis: Can Literature Change Us? I’m producing new poems, trying to write a play and a screenplay, hoping my wife and I can collaborate on a book. Every day presents more possibilities than I can seize.